Can community-led AI transform humanitarian communication?

A recent article on AI visuals in the humanitarian sector raises important concerns about charities using AI to generate images of poverty and suffering.

Despite ethical warnings, we know some organisations will continue using these tools. Could AI be used to generate synthetic images that counter the stereotypes that have plagued humanitarian photography for decades?

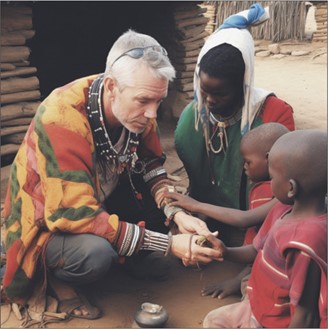

While the article notes that small NGOs in the Global South are using AI, it doesn’t consider the potential for organisations to collaborate with their communities in producing such images. There are promising case studies in “participatory photography,” where communities lead their own storytelling, like WaterAid’s Untapped Participatory Photography Project in Sierra Leone. Could co-creation utilising AI be an extension of this process?

Imagine a women’s cooperative in Bangladesh training an AI model on photographs they themselves have produced – visual material grounded in their own linguistic, cultural, and social contexts rather than mediated through Western development imaginaries. Such a practice could mitigate linguistic and cultural barriers in representation while foregrounding local knowledge and agency. Could local community-based organisations challenge stereotypes if they contribute to the AI tools?

Moving towards co-creation opens new ethical dilemmas: Who chooses which organisations and communities to work with? Who delivers training? However, organisations like Fairpicture and EveryDay Projects are already working to reduce these barriers.

Retraining AI with community voices

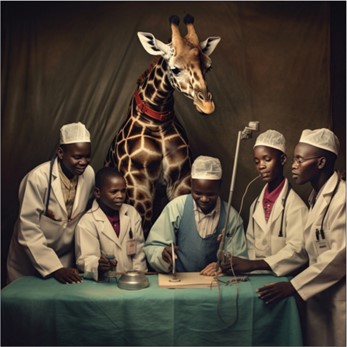

In 2023, researchers tested AI reproduction in global health visuals using Midjourney Bot Version 5.1. They attempted to invert stereotypical global health tropes by entering prompts for Black African doctors treating white children – but in over 300 attempts, the AI consistently failed, almost always depicting the patients as Black instead.

However, one year later (October 2024), I subscribed to Midjourney and ran the same prompts, which revealed measurable improvement. This suggests that representation in training data matters, and that giving local organisations tools to produce their own images at scale could meaningfully reshape how AI visualises communities in the Global South.

Maybe this is a controversial idea, but if local beneficiaries and community organisations received direct access to AI tools (perhaps sponsored by ChatGPT, DALL-E or Midjourney), they could generate thousands of images weekly reflecting their lived realities, cultural contexts, and self-determined narratives.

Current systems perpetuate harmful stereotypes because they’ve been trained predominantly on historical Western imagery. But as shown above, things are improving organically. If local organisations were funded to produce thousands of diverse, authentic images weekly, they would actively reshape how AI systems represent their communities.

If Microsoft or another major AI company offered funding to 50 community organisations in the Global South to generate 500 images weekly for one year, that’s hundreds of thousands of monthly counter-narratives. Microsoft recently announced a $30 billion investment in AI infrastructure in the UK between 2025 and 2028. Imagine if they invested £3 million (0.01% of their UK investment) to re-address biases in ethical representation. After all, the Gates Foundation has been committed to fighting inequities for 25 years.

The question isn’t whether AI-generated imagery is inherently problematic. It’s about who controls the tools, whose perspectives shape the outputs, and whether we’re willing to invest in community capacity to produce representations at a scale that can genuinely challenge entrenched biases.

Who should control the image? Surely the communities themselves.

Category

News & views