Tracing my path into peace photography

A few weeks ago, during a Making Peace Visible podcast I was asked about my journey into peace photography.

The conversation encouraged me to reflect on the path that brought me to this point and how I came to be part of our recently published Peace Photography: A Guide.

About a decade ago, a friend introduced me as her “peace photographer friend”. It made me laugh then but now it makes sense. The Central African Republic was entering a fragile disarmament process. I was there to work on a participatory video assignment with InsightShare and Build Up when a war photographer told me: “You cannot take pictures of conflict – the fights are over; there are no wounded.”That shocked me. I wanted to support communities to capture the legacy of war alongside the beginnings of hope.

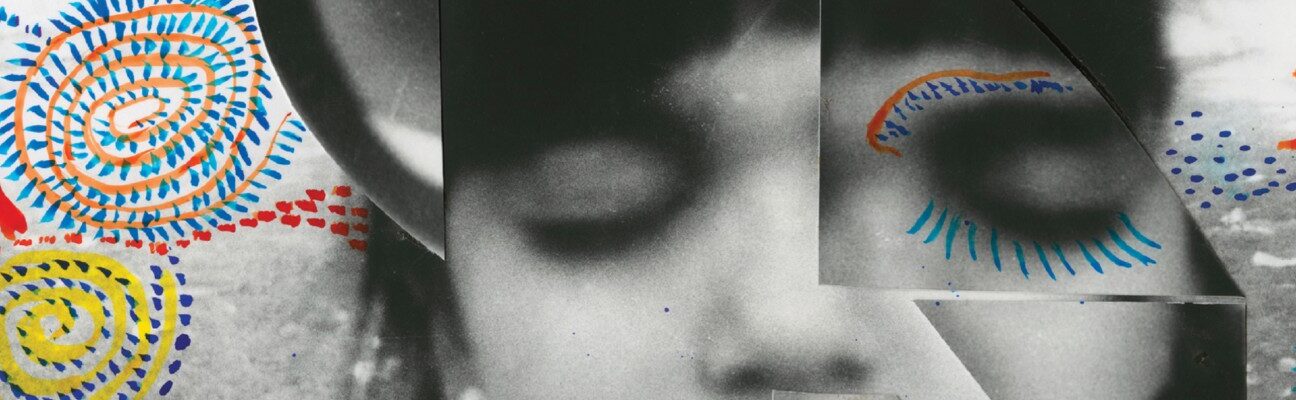

Around the same time, I was working with Mujer Diaspora, taking collaborative portraits of Colombian women. The FARC and the Colombian government had just signed their peace agreement. I had been living and working within the Colombian community in London, and I was constantly hearing stereotypes and daily discrimination tied to Colombia’s image. I wanted my photography to show the Colombia I knew – resilience, folklore, solidarity and joy.

Without realising it, I was already practising peace photography by transforming experiences of conflict and migration into narratives of healing, resilience and empowerment, giving women a platform to share their stories and foster reconciliation as women and peacebuilders, not victims. As Helga, Mujer Diaspora founder, says: “The peace of my imagination is possible if women finally enter the history of Colombia. We will achieve this by telling the stories of resistance, not the stories of war.”

Imaging peace

Years later, my long-time friend Dr. Tiffany Fairey invited me to participate in her Imaging Peace research to explore a simple but radical question, first asked by Fred Ritchin: What might the photography of peace consist of?

If you do an image search for the word ‘peace’, you’ll mostly find doves, V-signs, sunsets or AI graphics portraying stereotypical symbols of peace. Traditional photojournalism gives us frontlines and ceasefire ceremonies. But where are the human photographs of peace? The practice of peace photography shifts the lens toward something else: healing circles, reconciliation, communities rebuilding and everyday acts of solidarity. It reminds us that peace is not a moment but a daily, collective process – and it deserves to be photographed.

The research looks at grassroots community initiatives in places scarred by conflict. We examined how people were using photography to heal, resist, and rebuild. We collected nearly 30 examples from 21 countries, from Colombia to Kenya, Northern Ireland to Nepal. Out of this grew Peace Photography: A Guide – free in English, French and Spanish – and a website showcasing the diverse practices we uncovered.

The peace photography we explore is guided by the values of healing, dialogue, visibility, imagination and resistance. It takes many forms: photovoice projects, counter-archives, therapeutic photography and collaborative image-making. From Rwanda to Iraq, Turkey to Colombia, communities are reclaiming their stories and picturing futures beyond conflict.

What became clear is that peace photography isn’t just about showing peace – it’s about practising it. The act of creating and sharing images can involve dialogue, reflection and community-building, which is crucial for peace. In divided or traumatised contexts, photography can open small but powerful safe spaces for people to listen to each other, reframe their stories and imagine futures built on dignity and hope.

Peace photography in practice

The photographers we discovered came from many different walks of life. They included conflict survivors, peace activists, mothers, young people and former combatants. Some photographed their own communities, while others collaborated with artists across countries and continents.

What strikes me most is their intention: they aren’t just documenting pain but using photography to move beyond it. One Colombian participant from Tejiendo Vidas put it beautifully: “Sometimes we forget to share and interact with other people who also have many concerns and are in the same circumstances; we forget to focus on what we have in common.” Through participatory photography, she shifted her perspective from trauma towards resilience and the future.

Peace photography is a deeply ethical, fragile and complex action: it can work towards peace or create more conflicts and danger. Questions of consent, safety and power are crucial. Cameras have often been tools of surveillance or control, so trust and care are everything. As Dr. Fairey says: “Images shape our politics and societies. They can entrench division and normalise violence, but they can also nurture dialogue, heal divides and foster cultures of peace.”

Why does peace photography matter?

Peace photography isn’t only for photographers or for peacebuilding NGOs – it can be a powerful tool across the development and humanitarian sector. For organisations working directly in conflict and peacebuilding, it can:

- help people process trauma

- capture stories of healing and peace

- highlight conflict-affected communities, peace efforts and everyday moments of peace

- bring divided groups together to share and create new stories

- provide compelling visual evidence from the community’s perspective for donors, governments or international agencies, showing that change is happening

- promote trauma-informed, community-engaged photography practices which centre community voices and challenge old narratives, or build participatory visual archives which amplify voices and counter narratives.

Peace photography creates images that don’t just show what’s wrong but what’s possible, what is changing and the unnoticed daily work of resilience, rebuilding and collaboration.

If images of conflict show us what must end, peace photography helps us picture what must be built. That’s why it matters. It invites us, as photographers, educators, NGOs and storytellers, to make visible what peace might actually look like.

If you’re curious about what peace looks like – in your community, your country or your own life – I invite you to explore the guide, join the conversation and maybe even start making peace visible yourself.

You can download the guide for free here in English, French and Spanish.

Category

News & viewsThemes

Communications