Are the UK government going to lose the public with its latest announcement of UK aid cuts?

The UK aid budget faces its third cut in two years, as the government announced in November it will be slashed by another £1.7 billion in less than six months.

This came after the fiscal statement showed that the UK had spent more bilateral aid on its shores than overseas. Is it even worth trying to find a silver lining? If you’re interested in public opinion, then yes.

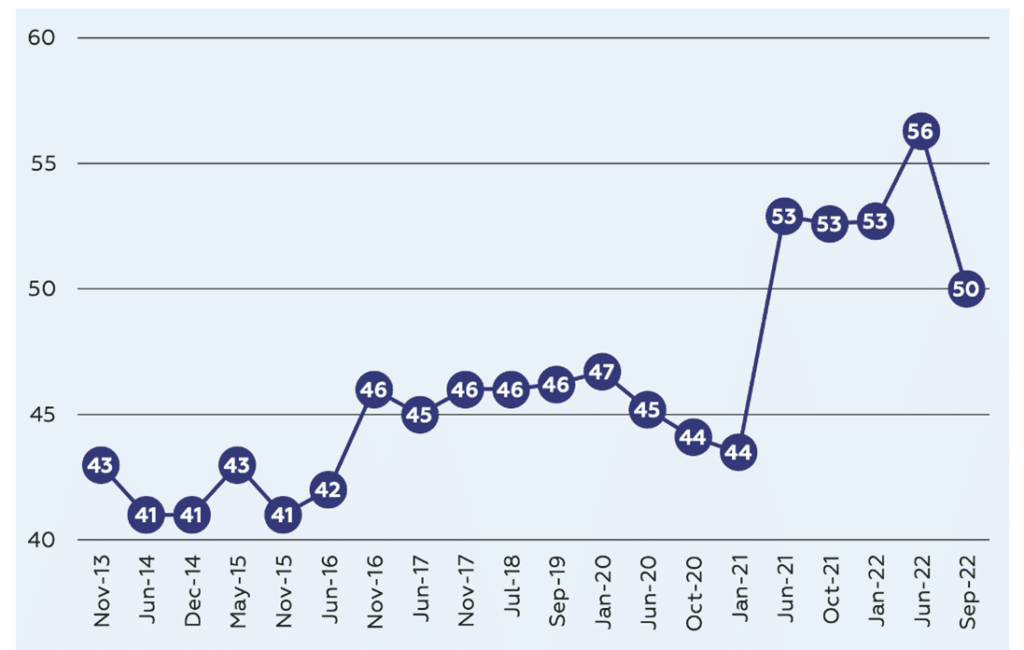

During the first big UK aid cuts, in June 2021, we at the Development Engagement Lab witnessed the biggest increase in British public support for maintaining or increasing the UK aid since we started tracking in 2013. Support tipped into the majority – 53% in favour of maintaining or increasing the budget. What’s possibly more surprising, is that as of October 2022, the majority of public support continues to hold.

Figure 1: Percentage of UK respondents who say they would increase or keep current UK aid expenditure levels

This begs the question: What will the public think about the newest round of cuts? Will they think they’re justified? And what does the public make of the government’s promise to restore the UK aid budget ‘when the fiscal situation allows’?

In 2021 and 2022, anticipating another round of cuts, we designed surveys to find out the answer to these questions, and I’m going to share those results with you.

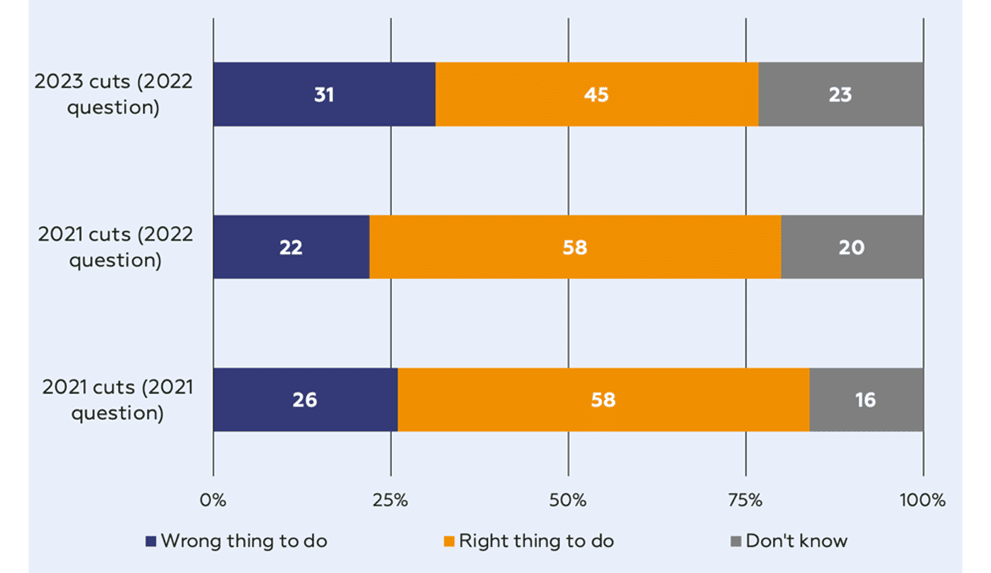

Figure 2: Public opinion on aid cuts from a 2021 question compared to the same question asked in 2022.

Was the decision to cut UK aid the right thing to do? 58% of respondents thought so, both in 2021 and 2022, according to our representative samples of Great Britain adults, interviewed online by YouGov in 2021 (4-7 June, n=1,656) and 2022 (14-15 September, n=1,746).

In 2022, we also asked respondents if they think cutting UK aid again in 2023 would be the right thing to do, and here no majority emerged, but the largest group (45%) thought cutting UK aid again would be the right thing to do.

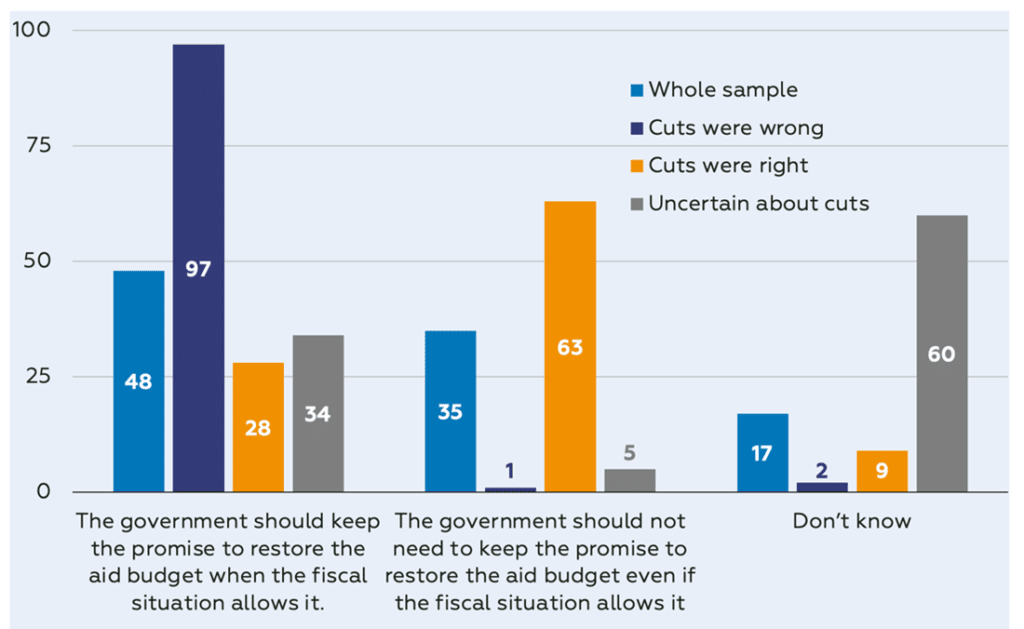

Figure 3: Public opinion on the government’s promise to restore aid expenditure levels in the UK.

What about the government’s promise to return to 0.7% of GNI spent on official development assistance ‘when the fiscal situation allows’, now also espoused by David Lammy of the Labour party? Here, more of the UK public (48%) says the government should be held to its promise than say they shouldn’t at only 35%, with 17% unsure.

The needle seems to tilt toward accountability. Breaking this down by past opinion and political affiliation, who is more likely to hold the government to account? Virtually all (97%) of those who thought the cuts were wrong in 2021 say the government should be held to its promise, as well as 68% of Labour supporters and 31% of Conservatives. Views on the government’s choice to cut UK aid clearly move along party lines, as does support for UK aid: 37% of Conservative voters are supporters, as opposed to 68% of Labour voters.

Considering the opposition and uncertainty seem to be higher when it comes to future cuts, plus the public’s clear desire to hold the government to account, we see space for campaigns and advocacy to make the most of these new majorities opposing further cuts.

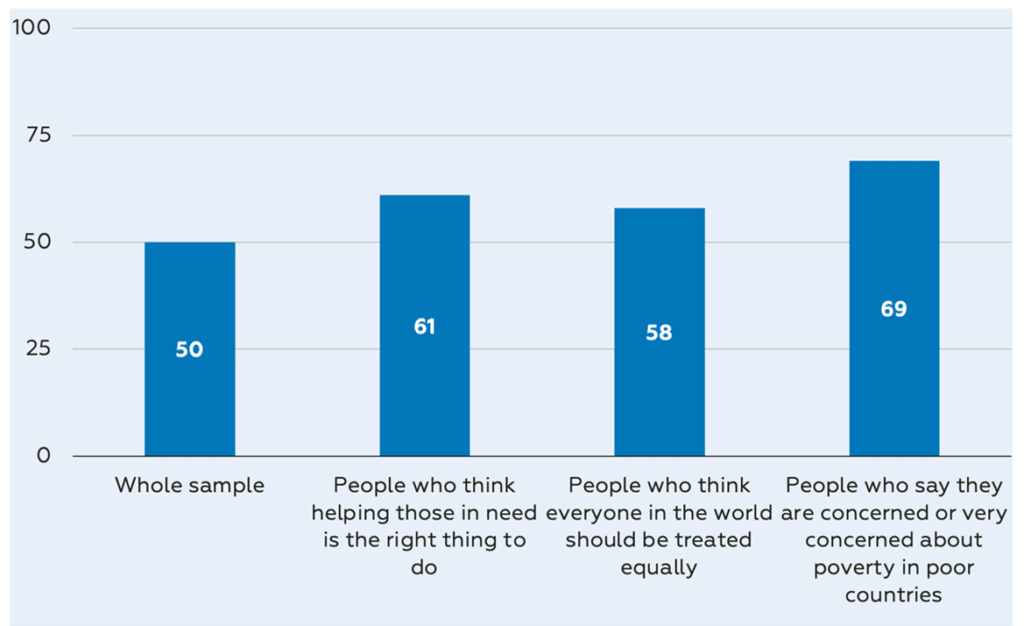

DEL has accumulated a series of insights on how to make the case for UK aid. We know people are more likely to support UK aid when they feel like helping people in need is the right thing to do (making the moral case for UK aid), when they hold strong egalitarian values that everyone around the world should be treated equally (making a value-based case), and when they are more concerned about poverty in poor countries (making a case to concerned audiences). We also know people’s support is shaped by their views on UK aid costs, benefits, and the efficacy of UK aid as a policy.

Making the case that UK aid benefits all parties involved, provides a return on investment, addressing concerns about corruption and waste head-on and that UK aid is an effective way to tackle poverty, will win support.

Figure 4: Percentage of UK respondents who say they would increase or keep the current UK aid expenditure levels broken down by moral views and concern for global poverty.

Finally, not all UK aid uses are the same in the public’s eyes. A majority of UK respondents think the main purpose of official development assistance should be reducing poverty first and foremost, while only 1 in 10 think UK aid should be used to promote national interests.

The highest UK aid priorities for the public are consistently access to water, health provision and education. Here the views of the public clash quite a bit with the newest announcements from the government. Cuts to bilateral aid in favour of supporting refugees in the UK could be seen as a constraint on the UK’s ability to deliver on healthcare, access to water and provide real help for low-income countries.

The next months or years could drastically change the nature of the UK’s contribution to global development. The voice of the public will be essential in guiding policymakers and reminding them to strive for a balanced approach to tackling global poverty.

Category

News & Views