The future of big INGOs: ways forward in a fast-changing world

What is the future of large, billion-dollar, multi-mandate international development NGOs? In my last blog, I looked at whether large INGOs can survive and thrive again.

Drawing on my research with big INGOs, I’ve identified some ways forward for INGOs to adapt to a changing operating environment (which I’ll also be exploring at the Bond Conference).

Why change? Trends transforming INGOs’ operating contexts

The face of poverty is changing and with it the demands and needs of our clients.

- As poorer countries become more stable and their economies grow, NGOs aren’t needed to deliver services or programmes. Big NGOs can support effective local agencies and local government to deliver services with knowledge and resources. Poorer communities may need support to influence national and global decisions that affect them locally, such as climate change, trade rules, tax laws and security. Big NGOs need to rethink their relevance and added value in advocacy and in networks with client-led platform solutions or consultancy services that enable others or support coalitions.

- Conversely, so little has changed in fragile, conflict-affected states, where INGOs struggle to make lasting impact without effective governments. Aid is increasingly going to fragile states, but it’s harder to convince supporters of the value of our work in unstable states where we struggle to have impact on appalling levels of poverty. We need to work collaboratively to take a whole-system approach, testing learning and adapting innovative approaches to build the peace dividend and tackle chronic poverty. Large INGOs could play a key role in convening this collaboration and agreeing how best to divide labour in a fragile state, rather than competing for uncoordinated donor contracts.

- With the rise of populism in Europe and US, INGOs need to reassess what’s needed in their own constituencies too. INGOs need to re-engage with the public in a different way – perhaps leading a debate about what sort of world we all really want to live in. While few issues can be rectified or policies changed just by clicking to join a petition or campaign, much can be achieved on a small scale through community action. INGOs need to collaborate with clicktivists and movements as they arise to lend support and co-create campaigns. With less public and even less political support for their advocacy mandate, such campaigning functions need to use less resource more wisely in order to leverage more on universal issues that really matter to people.

- With increasing conflict and the impact of climate change, demand for humanitarian response is rising. As the Grand Bargain1 recognised, humanitarian action needs to be more localised, more innovative and should find political solutions to the root causes of humanitarian needs.

Options for changing your organisational structure

Given these likely paths for the future, multi-mandate INGOs need to make some significant practice and cultural changes. Reorganising can help. In my research, I looked at examples of how digital organisations, big business and large UK charities are restructuring, and the pros and cons of these changes. These are the structural options I’ve identified:

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network News1. Fragment

Organisations can split into smaller, empowered, more independent, more agile, more manageable business units. This can be achieved through either:

- Selling off assets to enable independent businesses to thrive and raise investment capital.

- Focusing only on the part of the value chain you do best rather than doing everything yourselves

- Becoming a group or franchise of independently run businesses, with their own boards under one group brand, whilst being bound by brand values and rules.

| Pros | Cons |

| Separate smaller businesses are more manageable2 and more agile, enabling more innovation and specialism within each function. They protect one part of the group from asset risks in another (though not necessarily reputational risk). They offer the potential for a more efficient structure for a large INGO to consolidate its business support, compliance and financial risks; to facilitate opportunities for growth; and to build on the existing internationalisation of large INGOs. | These structures are far more complex, and so take more time to make decisions. It is challenging to manage brand/reputation risk, the risk of association, and interdependent compliance. Complex matrix leadership is expensive, and requires significant investment. It can lead senior leaders to be very internally focussed. With growth, maintaining the group’s culture becomes a challenge. |

2. Consolidate

Organisations can acquire the skills or assets needed to respond to change. This can be achieved through either:

- Acquiring organisations that have the skills/contacts/approach needed.

- Merging with others that have matching skills sets to gain scale or new skills or eliminate duplication.

| Pros | Cons |

| Improved financial growth and sustainability; enables organisations to acquire new assets/capabilities more quickly; enables more control of market share; reduces competition; is less confusing for end users/clients. | Takes on historical risks (many unknown); loss of brand, especially for an acquired organisation; challenge to merge two organisational cultures; reduces consumer choice; makes large organisations even larger and harder to manage. |

3. “Unbound”

Organisations provide platforms to enable others to connect, and add value through convening, triaging, or quality control. This is more of a “reboot” or “start again” option.

| Pros | Cons |

| Makes use of a recognised brand, keeps agile, exploits gaps in new emerging markets. | Requires different skills sets and mind sets and increased risk appetite. Innovation needs autonomy, risk taking and freedom to fail. Greater risk appetite might be difficult for bureaucratic INGOs under compliance pressures. |

Different structural solutions could be applied to different INGO functions, more of a ‘pick and mix’ approach to change, rather than any of the more radical options being applied across the board.

So what’s stopping INGOs from changing?

While none of the large organisations I spoke to considered that it was an option to retain the status quo in our fast-changing world, and all considered making tough choices a necessity, not all thought they needed to change so radically.

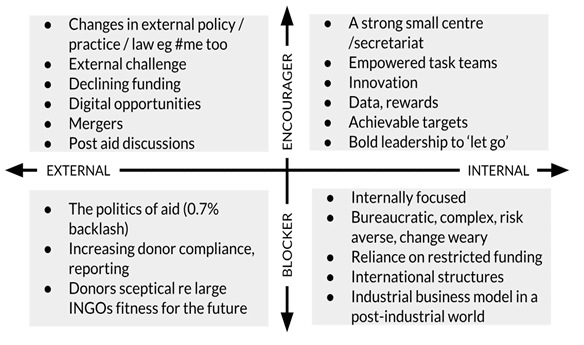

INGOs I interviewed either disagreed on how much they need to change, or CEOs were frustrated with the many blockers they felt were preventing them from changing. Below are the factors that those I interviewed saw as either preventing or encouraging positive change:

It takes such bold savvy leadership to transform an organisation. At the Bond Conference 2019, I’ll be exploring how big INGOs can rethink their models.

Such rethinking takes courageous leadership – and that’s the focus of my next research. I’ll be analysing what it takes to be courageous as a leader, reflecting on what our INGO sector needs to learn, how to make it happen and the unequal gender dynamic in leadership roles. Anyone interested in sharing or collaborating – do let me know.

Notes

1 – The Grand Bargain (2017) is an agreement between more than 30 of the biggest donors and aid providers, including the UN which aims to get more means into the hands of people in need.

2 – Robin Dunbar holds that in an organisation of more than 150 people find it difficult to form relationships or maintain emotional connection

Category

News & views