Theory of change for advocacy and campaigns

Type

VideoThemes

Public SupportJenny Ross introduces the four simple questions that could transform your advocacy strategy and increase your impact.

Working in advocacy and campaigns, we all want to influence change. But is what we’re doing really contributing to the change we want to see?

Using a simple theory of change approach can help you to make the connections between what you’re doing and the change you want to see.

If you’d like to learn more about how change happens, and how to demonstrate the impact of your advocacy, book a place on our two-day course.

Overview

As campaigners and advocates we try to influence change and make a difference on the issues, and for the people, that we care about. However, processes of change are complex and unpredictable, so it is often difficult to decide exactly what to do.

Faced with this complexity or messiness, when planning campaign strategies, we often try to simplify by:

- identifying a problem and a solution;

- producing campaign messaging, policy proposals and research which supports the analysis; and

- communicating core messages to as many people as possible using multiple channels (media, lobbying, social media, supporter mobilisation, etc).

This approach means that we keep busy and get a lot done. But lots of activity doesn’t necessarily translate into influence or change, and it can be difficult to understand and measure effectiveness and impact.

This is where theory of change can help. It makes the links between what you are doing and the change you want to see.

The benefits of a theory of change approach

Developing a theory of change can help you to:

- “zoom out” and better understand your role in the context of the broader processes of change;

- reflect on and theorise about how change might unfold and what role you can play in it;

- build a common understanding within your team and strengthen critical or evaluative thinking which is vital for effective advocacy and campaigning;

- remain focused on the change you are working towards and how what you do makes a difference, so when the context changes you don’t lose your way;

- strengthen your understanding of your progress and results and your contribution to change; and

- develop a framework for measuring your learning and effectiveness.

Developing a theory of change

A theory of change can be developed at many levels: for a coalition, for a whole organisation, for a team, or for an individual campaign or advocacy initiative. The process of developing a theory of change should be participatory – it should involve reflection and discussion in a group setting. Below you’ll find some exercises that can be used to facilitate and shape these discussions.

A theory of change should consist of more than a diagram! The collective thought process is critical and the final summary diagram should be accompanied by a narrative explanation of how, and why, you think change will happen.

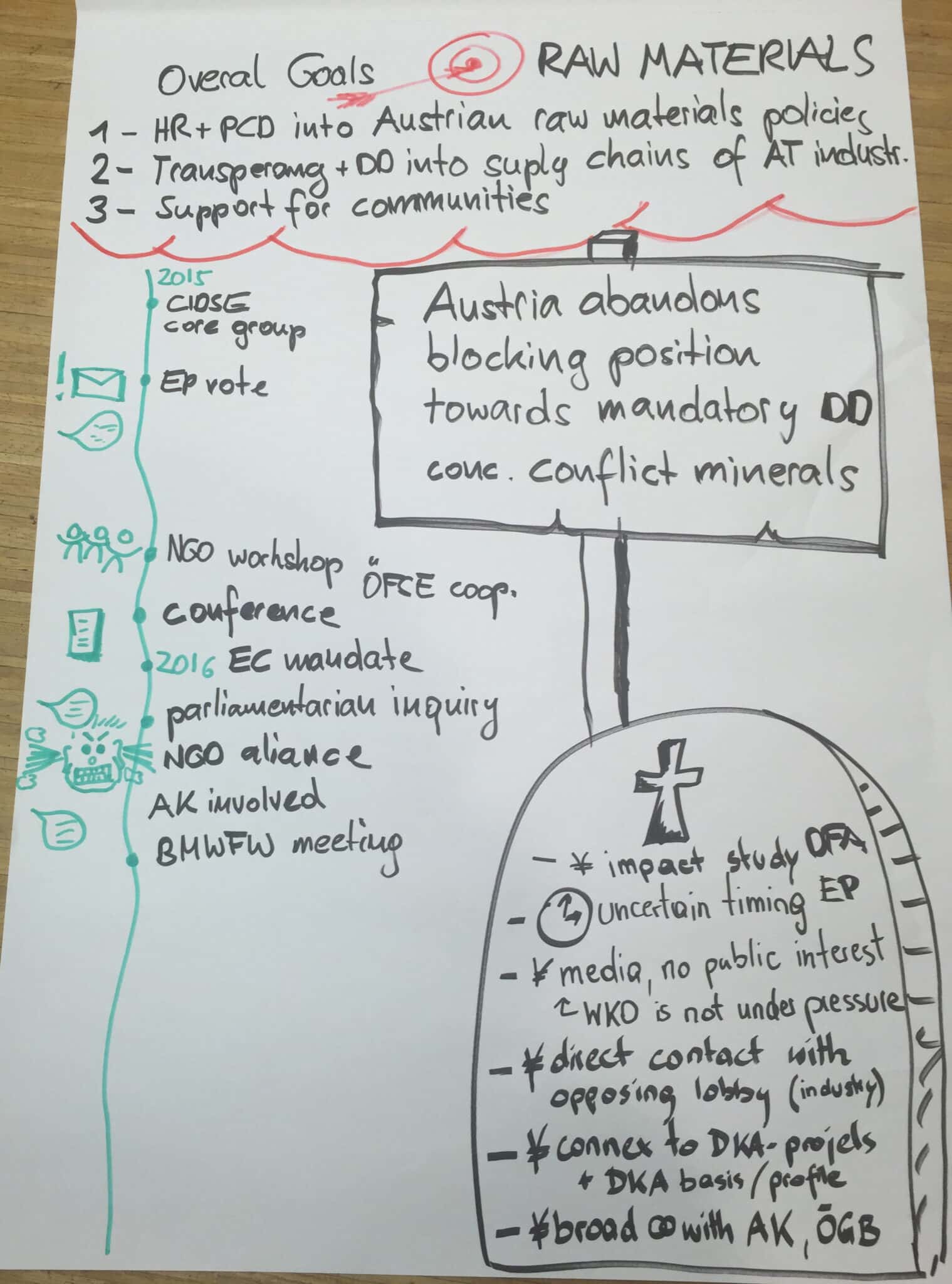

A simplified theory of change process involves asking four key questions:

- What is the overall change?

- What are the pre-conditions?

- What is your contribution?

- What does progress look like?

1. What is the overall change?

This question invites us to zoom out to the bigger picture impact; it goes beyond our own contribution and should be set at least three years in the future, if not longer depending on the critical timescale for the issue.

Newspaper headline exercise

Asking participants to imagine what the newspaper headline will be on the day that the campaign or advocacy initiative succeeds clarifies the overall change. Develop headline ideas individually, then share the ideas as a group and discuss any similarities and differences before agreeing the overall change collectively.

2. What are the pre-conditions?

These are the changes that need to happen before the overall change can come about. They are also called critical success factors.

It is often easiest to consider these as the flip-side of what the obstacles to change are.

For example, to make progress towards ending climate change, the following changes will be critical:

- government and private sector investment in alternative energy;

- adoption of carbon pricing;

- international cooperation that leads to a globally owned solution; and

- the end of fossil fuel subsidies.

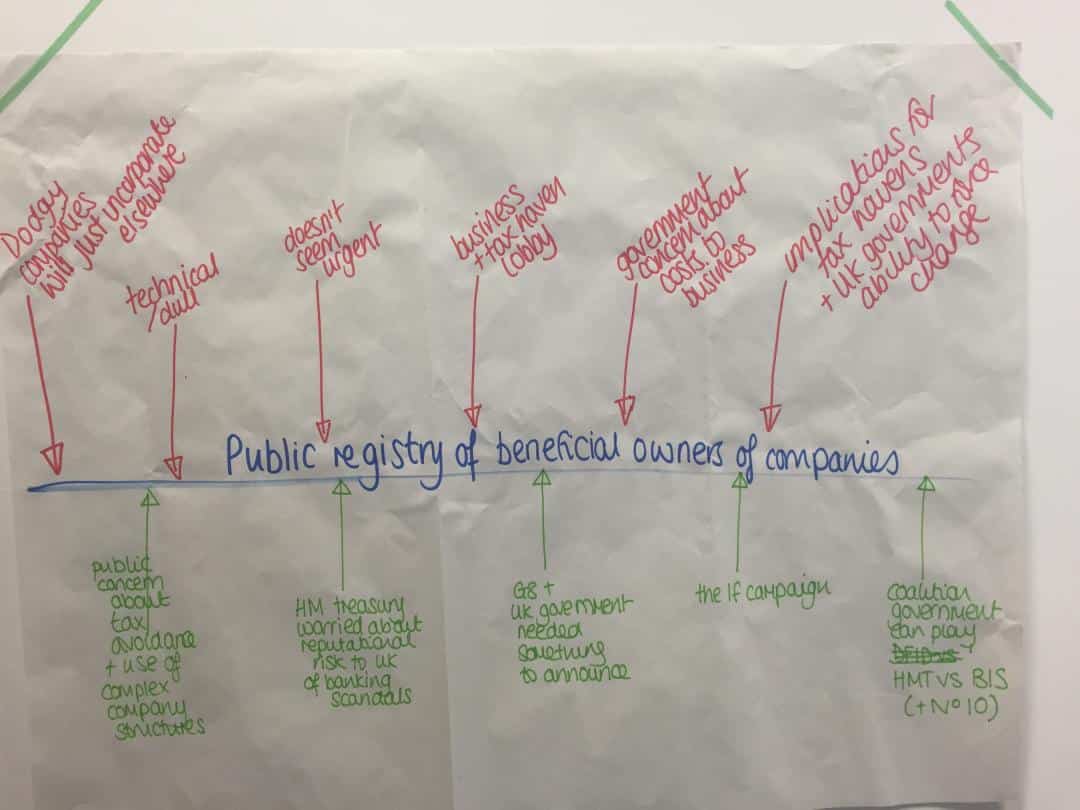

Forcefield exercise

It is important when identifying the pre-conditions to consider the change you are going to make and the specific context within which you are working. There is a wide range of context and problem analysis tools which may be useful. A forcefield analysis can help participants to identify the pre conditions.

- Draw a line down the middle of a piece of paper and write the overall change on it.

- Discuss and map the forces or factors that support change (in green) and progress on the issue and those which constrain it (in red).

- Use the mapping to identify the 3-5 most significant areas where change is needed in order for the overall change to be possible.

3. What is your contribution?

Several organisations might share an analysis of the overall change and the pre-conditions, but their contribution to that change will be dependent on their own knowledge, skills and experience.

For example, lots of different groups and organisations want to reduce fossil fuel pollution. But they contribute in different ways.

- Art not Oil is contributing to change by trying to end oil company sponsorship of the arts.

- 10:10 is contributing to change by trying to create a constituency for climate action in the UK.

- The Climate Coalition is contributing to change by trying to mobilise UK citizens to put pressure on their politicians to take action.

- Divestment campaigns contribute to change by getting individuals and institutions to withdraw their investment from fossil fuel companies.

It is important to clarify where you think your organisation’s specific contribution will be (the added value) so that you can understand your impact, alongside that of other organisations working towards the same overall change.

Your organisation does not necessarily need to be contributing to all of the pre-conditions but it is important that you understand how the broader change will happen and which other organisations are contributing in areas that you are not – otherwise your efforts might be wasted.

Exercise

You can map your potential contribution/added value by discussing your organisation’s knowledge, skills, experience, relationships, etc. You can also reflect on your previous campaign and advocacy successes and failures and where you have been most successful and why.

Clarifying your theory of change

Before you begin to think about what progress would look like in terms of your campaign or advocacy initiative it is important to summarise the implications of your answers to the first three questions.

Example of a narrative theory of change: Fossil Free Campaign

What is the overall change?

Stop the negative impact of fossil fuels on climate change and the environment.

What are the pre-conditions?

- A movement that acts as a countervailing force/power to those who benefit from the status quo.

- The availability of sufficient investment in sectors which reduce dependence on fossil fuels and promote clean energy.

- Reduced incentives to invest in fossil fuels as a result of increased transaction costs and associated reputational risks.

- The adoption of carbon pricing.

- International cooperation that leads to a globally owned solution.

- The end of fossil fuel subsidies.

What is the contribution?

The Fossil Free Campaign contributes to the creation of a broad movement and shifts in investment as it encourages students to put pressure on their universities to divest from fossil fuels and invest more sustainably.

4. What does progress look like?

Before you get started on implementing your strategy and planning your activities, a theory of change approach encourages you to think at the outset about how you would know if you were making progress and to set out a change pathway.

Identifying what changes you would expect to see over the short and medium term is very important, because it is hard to talk about progress and your contribution if you are only looking at long-term change. It can also be demoralising. Without outlining these steps towards change you risk focusing too much on what you are doing, rather than what you are changing.

You want to try and think about how progress can be tangible or visible – what would people be doing or saying that is different to now?

For example, if you have identified that your strategic contribution will include trying to engage with policy makers to change a policy, you may notice small markers of progress:

A government official or member of parliament, who has previously refused to meet with you or has ignored your emails, now wants to meet.

The discussion that you are having with policy makers is no longer about whether the problem exists, but focuses on how it can be addressed.

You can develop this further into a change pathway, which maps from your activities through the changes – sometimes called intermediate outcomes or milestones – to the overall change.

There are many ways in which organisations can trace their contribution and progress, not just in terms of policy change. For example, advocacy and campaigns can:

- Strengthen civil society voice or the collective strength of civil society

- Strengthen citizens’ understanding and empowerment

- Generate new knowledge and information which can be used to influence change

- Create new structures and spaces for dialogue and engagement between civil society (or citizens) and government

- Change attitudes or social norms

- Set new precedents in relation to the behaviour of governments or other actors

Often, campaigns and advocacy initiatives are unrealistic in their expectations about the pace of change, or they focus around key “moments” without a clear sense of what the change is or what it is expected they will deliver.

It is helpful to set out what changes you would expect to see over the short, medium and long-term, how you would know if you had achieved them, and how you would show that progress to others.

Linking your activities to progress and impact

If you already have campaign or advocacy activities planned you can make these more progress- and impact-oriented by simply asking what you want to change as a result of the activities you have planned eg if you are attending a conference, ask why, and what progress or change will be achieved; if you are launching an e-petition, ask why, and what progress or change will be achieved.

If you don’t already have activities planned, or you have some flexibility within your existing plan, you can ask: what could we do that will contribute to the progress that we want to see? This should be based on the analysis outlined in your theory of change – both how change will happen but also your contribution to that change.

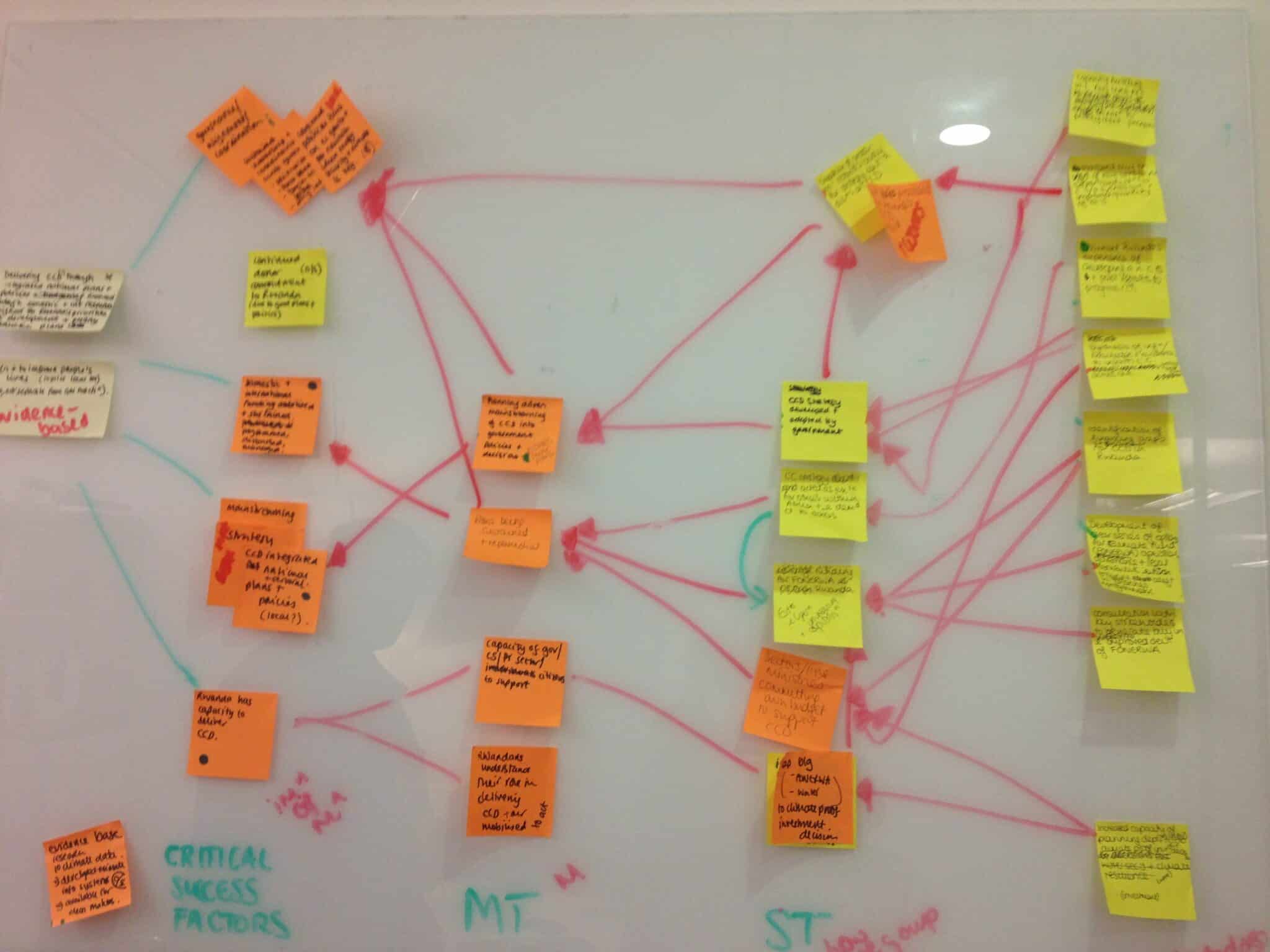

Exercise

You can map out these signs of progress by having a group discussion and writing them on Post-it notes or paper plates. Arrange them in terms of whether you think they will happen over the short, medium or long-term.

Then use more Post-it notes or paper plates to link your activities to those signs of progress.

If you have activities that don’t seem to be contributing to the change you want to see, you may need to re-consider their value as part of your strategy.

Similarly, if you have identified progress that you want to see, but you haven’t planned any activities to influence that change then you may need to add additional activities or adapt existing ones in order to have impact.

Testing your theory of change

Once you’ve set out your theory of change it is good idea to stress-test it before you start planning your activities.

The simplest way to do this is to get someone who hasn’t been involved in the process to take a look at it and see whether it makes sense to them. Or, you can invite experts in your area or coalition partners to review it and provide comments.

You want to understand where you are confident in your strategy and the likelihood of progress, because you have evidence that change is likely or learning from previous campaigns can be applied, and where there are areas of uncertainty or assumptions being made.

Identifying assumptions is an important element of developing a strong theory of change. An assumption is something that you believe to be true without evidence or proof. Common assumptions which that are made in advocacy and campaigning are:

- if we conduct research that shows that our issue is a problem it will lead to policy makers taking action on our issue;

- if we raise public awareness of our issue it will lead to the public putting pressure on policymakers or becoming active supporters of our issue; and

- the context will stay the same or it will change.

It is impossible to develop a theory of change that contains no assumptions, but it is important to consider what evidence or learning you have to back up the assumptions that are inherent in your proposed approach and how you can manage or mitigate risks.

If you have mapped out your theory of change and activities you can trace all of the connections that you have identified and highlight those which are most based on assumption/least evidence based.

Premortem exercise

The point of a premortem is to break through the bias of unwarranted optimism. As described by decision scientist Gary Klein, a premortem is “done at the beginning of a project rather than the end, so that the project can be improved rather than autopsied. Unlike a typical critiquing session, in which project team members are asked what might go wrong, the pre-mortem operates on the assumption that the ‘patient’ has died, and so asks: what went wrong. The team members’ task is to generate plausible reasons for the project’s failure.”

By stipulating that something has already failed, you free people up to express doubts and critiques they may have been harbouring, but did not feel at liberty to express. You unleash the devil’s advocates.

Once you have developed a strategy or a theory of change, introduce the idea of undertaking a premortem to uncover risks and assumptions and try and understand how you can improve your strategy.

Imagine that you are giving a presentation to your board, your managers, or your funders in three years’ time, or however long your strategy lasts for. The strategy has been a failure; you can’t show evidence of progress or results.

Prepare a presentation documenting what you learned, what you would do differently and what advice you would give to someone considering a similar initiative.

If you think that the approach is too negative then you can divide those taking part into two groups and ask one group to prepare a presentation about why the strategy has been such a success and identify why.

Using your Theory of Change for reflection and learning

The process of developing a theory of change is resource-intensive. Don’t just leave it on a shelf. It is helpful to use your theory of change to frame discussions about progress and impact. This can support learning and also help you to strengthen effectiveness and impact.

Exercise

Either on a regular quarterly or half-yearly basis, or after a major peak of activity, it can be useful to review progress against your theory of change in a meeting.

Results and impact questions

- What was achieved over the review period?

- What was the organisation’s contribution?

- What evidence do you have that the change has occurred or that progress is being made?

- What were the factors that contributed to the outcome? (positively and negatively)

- How did you adapt your strategy based on changes in the context?

- What does the change mean?

- How does it link to the overall changes that we want to see in the world?

Process or implementation-focused questions

- Which activities worked particularly well and why? Which activities did not work, or went badly and why?

- What particular challenges or constraints were faced? Were these overcome? If so, how? If not, why not?

- What particular opportunities were seen in the course of strategy? Were they taken? If not, why not?

- Did any new ideas and innovative work arise out of the strategy?

- What lessons were learned? What has been learned from others working in the same fields or areas?

- What would you advise someone to consider when planning a strategy on a similar issue?

- How were resources for the strategy invested? Which activities delivered the best “bang for buck”? Which were potentially over, or under, invested in? What were the consequences of the level of investment?

Further Reading

Theory of Change Thinking in Practice | Hivos

Campaigning for change: Learning from the United States | Brian Lamb

How change happens training course