How can we work together to realise the promise of human rights 75 years on?

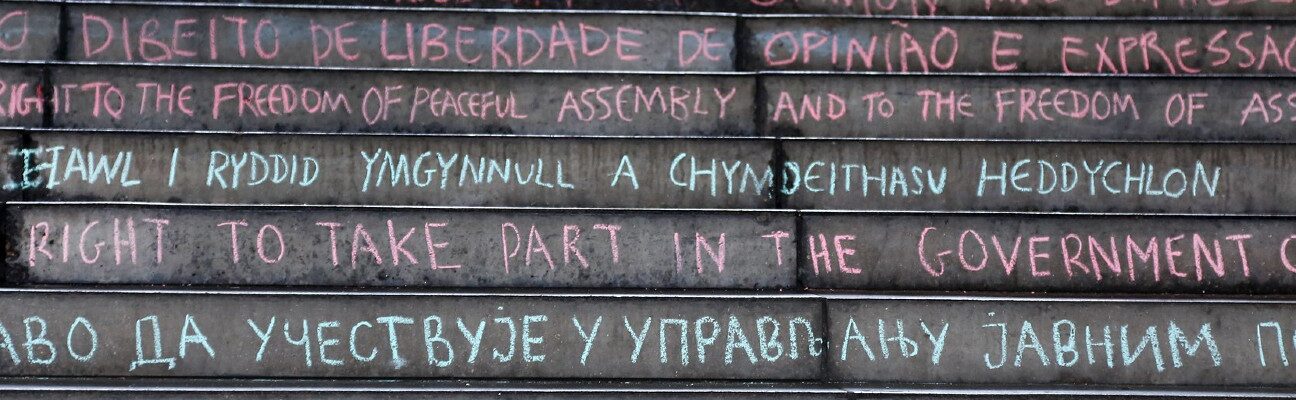

This month marks 75 years since the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the foundational document of all subsequent human rights laws and policies.

It is clear that many states are falling dangerously short of the document’s historic promise. But activists on the front lines, such as those we support at the Fund for Global Human Rights, remain motivated by the same core principles found in the UDHR: dignity, equality, and freedom.

Through grassroots work, they strive to turn the declaration’s potential into real progress. But they face unprecedented danger, including persecution, imprisonment, and even death.

As we pause to reflect on 75 years of human rights policy and practice, we are calling on funders and civil society to unite around a bold vision for the future of human rights. Amidst immense global challenges—including conflict, climate change, and rapidly evolving technology—we must redouble our support for local activists and renew our commitment to the next 75 years of human rights.

Here are five key areas that will be critical for the future of human rights.

Changing narratives around security

National security agendas are all too often manipulated to criminalise and disrupt human rights work. There has been a growing trend of governments using the veneer of national security to consolidate control and stifle dissent.

In the UK, we have seen this starkly in recent years: from the emergency legislation during the Covid-19 pandemic through to government crackdowns on the rights to free assembly and protest, the right of workers to withdraw labour following a democratic strike ballot, and the rights of local councils to make investment decisions on human rights grounds. Just in the last few weeks we have seen ministers posing existential threats to the Human Rights Act itself in relation to the Supreme Court’s decision on the proposed Rwanda scheme.

There is a global trend towards securitisation and criminalisation of human rights. The world is becoming a more dangerous place for activists: Front Line Defenders found that 401 human rights defenders were killed in 2022, compared with 358 deaths in 2021. We need to push collectively to reverse this trend–and this means calling for a new security agenda that brings to the foreground the safety of rights defenders and the most marginalised groups.

Countries that position themselves as democratic and open societies must lead by example. Through the recent UNGA Third Committee Resolutions on Human Rights Defenders, the UK government has made sweeping commitments to protect human rights defenders and keep space to protest open. These reinforce commitments previously made at the Summit for Democracy and through Sustainable Development Goal 16. As civil society, our responsibility is to hold policy-makers accountable to these commitments.

Funding movements effectively and shifting power to the grassroots

The architects of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights believed that governments would lead the way on human rights. In practice, however, grassroots activists have been at the forefront of change while states have relinquished much of their responsibility to civil society, philanthropy, or the private sector.

At the Fund for Global Human Rights, we work with a network of hundreds of global activist grantee partners. Unsurprisingly, their views on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are diverse, but what these groups share is the same vision, creative thinking, and belief in a better world that brought the declaration to life. They also, sadly, share another thing: a lack of resources and support.

In a recent survey of Fund grantees, only 35% said they were financially prepared to expand or even sustain their current work. Over half anticipate making at least some cuts to their programming. And the vast majority—70% —said they receive mostly restricted funding that cannot be applied to essential operating costs, including staff salaries and office space.

To shift power to the grassroots, we must transform and scale resourcing for grassroots civil society to be sustainable and reverse the historic power dynamics that keep local movements from realising their vision. There are many aspects to this, but long-term, flexible funding is an essential part that the UK charity sector is still falling behind on. Without such funding, many of the most effective civil society actors—such as decentralised mass movements or unregistered organisations working in remote locations—are unable to adapt to changing contexts and take ownership over the issues that most impact them.

Ensuring a rights-based response to the climate crisis

Our collective response to the climate crisis must go beyond just cutting carbon.

Climate change is a major threat multiplier: Populations who are already vulnerable—due to geography, conflict or intersectional oppression—face the worst impact. The consequences of climate change, such as eroding coastlines and destroyed ecosystems, deepen inequalities, meaning those who are least responsible for the crisis are also least able to adapt to its threats.

The transition away from fossil fuels must equitably redress past harms, via mechanisms such as a Loss and Damage and Adaptation funding. These mechanisms must be set up to work in the terms of Global South civil society groups. A truly just transition cannot be adopted or imposed from above. Instead, the people and communities most affected by climate change must have a voice in any economic development that affects their land and livelihoods.

It is vital that donors and civil society work together to build solidarity across border and sectors and provide security to at-risk environmental defenders. In the UK, it‘s likely that issues around climate will be pushed as part of a divisive ‘culture war’ narrative in the run up to the 2024 General Election. As civil society, we need to support groups that tell a more hopeful story on climate, and push back against harmful narratives that paint climate activists as terrorists or criminals.

We need to ensure that environmental defenders can exercise their core freedoms under national and international human rights standards, and that women, young people, Indigenous groups and poorer communities are empowered to work together in solidarity for long-term change.

Realising economic justice for all

While civil society has taken up the mantle for many governance failures, we have historically been too weak as a sector on a central tenet of human rights: economic justice. Historically, many have seen socio-political rights as distinct from economic rights, but the reality is that they are inseparable. Many in civil society have shied away from this conversation for fear of being seen as too ‘political’ or ‘radical’.

Many of our grantee partners are actively working to reimagine our global economy—from undertaking cost/benefit analyses of local development projects to advocating for collective worker protections in dangerous industries. These are actionable alternatives to our failing status quo.

Activists are imagining an economy that is centred on wellbeing and in equilibrium with the natural world. As a movement, we can no longer shy away from radical solutions to economic injustice—instead, we must push funders and governments to recognise their utility, embrace creative solutions, and provide funding to movements that are building alternatives from the ground up.

Innovating for the future of activism

To be truly equitable and effective, rights work needs to be constantly evolved, shaped, and re-imagined by the communities who are most impacted by violations. That means centring youth-led movements, testing new and innovative forms of activism, and being prepared to take risks in our funding and policy-making.

Young people have innovative and creative responses to the challenges we face in our communities, from unemployment, to violence against women and girls, to the climate emergency. But too often, their voices and contributions are not taken seriously—or even persecuted for speaking up.

Young people possess immense power to shape their own destinies and transform their communities. We must centre youth, not merely as recipients of aid, but as critical agents of change who can meaningfully influence decision-making processes and create innovative solutions to pressing challenges.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Civic space