Why we need “durable solutions” for internally displaced Ukrainians now

Today marks not only 31 years of Ukraine’s independence but exactly six months since the escalation of the war.

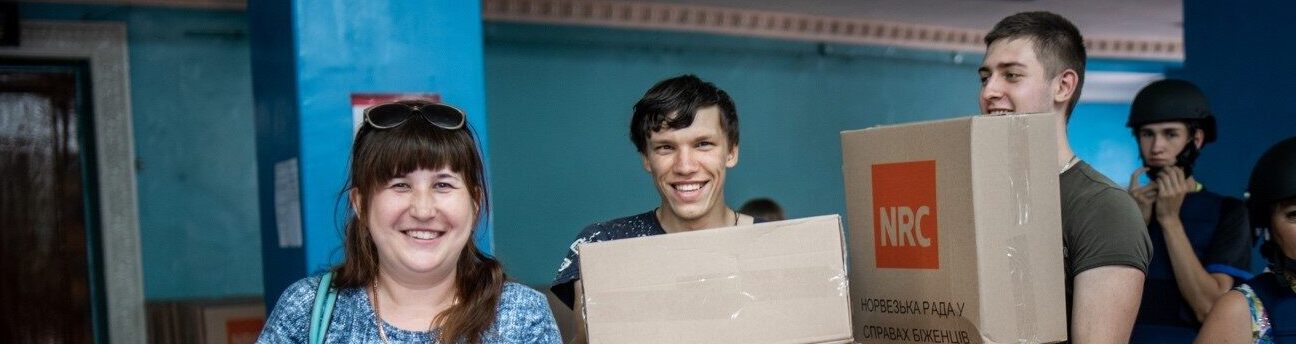

Communities in eastern Ukraine have been divided by a frontline since 2014 when the war began. Severodonetsk, Stanytsia Luhanska, Sloviansk, Avdiivka and Kramatorsk are now globally recognised as places where the horrors of this war are playing out. But the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and our Ukrainian partners had been working with communities there since 2014. And we’ve seen the damage short-term thinking can have on the lives of internally displaced people.

Counting the costs

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reports that in the past six months, over 5,500 civilians have been killed in Ukraine and at least 13,212 injured. The real numbers are likely to be even higher. Many others have lost or fled their homes in the fastest growing – and biggest – displacement challenge Europe has faced since World War II. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), at least 6.6 million people are currently displaced inside Ukraine, and over 11 million have crossed an international border in search of protection and assistance. The Displacement Tracking Matrix estimates 5.5 million people have returned home in the past few months. Despite the unpredictable situation, for some displaced people homesickness and the desire to reunite with their families is outweighing personal security concerns.

With such fluid displacement, one might argue this is not the right time to talk about durable solutions. These are solutions that stop internally displaced people from having specific assistance and protection needs linked to their displacement, meaning they can enjoy their rights without discrimination.

From my experience, both professional and as a Ukrainian who has twice been displaced, it is never too early to start this conversation. On the contrary, in a context like Ukraine, where every fourth citizen is displaced, it is important to think about durable solutions as early as possible. The lessons from other countries, and indeed from Ukraine’s own displacement experience since 2014, prove that failing to incorporate long-term, durable solutions at the start of a crisis increases the likelihood of protracted displacement, which is harder to remedy.

Avoiding past mistakes

Despite the ongoing war, discussions about recovery are already happening in Ukraine. Ukraine’s strategy on internally displaced people, adopted back in December 2021, is now being revised to meet the current scale of displacement and needs. The revised strategy is expected to cover not only the situation of people displaced inside Ukraine, but also returnees from abroad. Other broader policy or legislative processes – related to housing, restitution or compensation, social protection and employability – are either in discussion or already active. This creates momentum to include durable solutions in Ukraine’s new national recovery frameworks and embed a rights-based, whole-of-government approach.

Prior to the escalation of the war in February, over 750,000 people were already living in protracted displacement. It is important to prevent the obstacles these people have faced from being replicated. We found national authorities often lacked information about people’s specific displacement-related needs, locations and conditions. Internally displaced people who had integrated locally found they could not relinquish their official status as internally displaced people (IDP) and maintain access to services, social benefits and pensions. “Once an IDP – forever an IDP,” we used to say.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsMore egregiously, people who were not displaced but lived in places not controlled by the government had to register themselves as displaced to access their rights and services in government-controlled areas. As of December 2021, nearly 6,200 internally displaced people were living in collective centres, often in dire conditions, while many more struggled to find longer-term employment and housing.

It took local civil society actors and international organisations four years of advocacy for internally displaced people to be able to vote in local elections. But the voices of displaced communities were still not being heard and they lacked ways to practically influence decision-making.

A way forwards

The mistakes of the last eight years can be avoided. But this will take the creation of needs-based assistance, data-driven policies, and the inclusion of internally displaced people in designing, implementing and monitoring the policies and practices that affect them.

We already have tangible evidence from eastern Ukraine of the benefits of coordination and planning between local, international development and humanitarian actors, including within pilot humanitarian-development interventions. This local expertise, leadership, experience and knowledge still exists. This provides a solid basis to re-think “traditional” approaches and instead develop humanitarian and recovery frameworks that can co-exist and complement each other. Such frameworks can support the durable solutions displaced communities need, and achieve sustainable and cohesive recovery in Ukraine.

Category

News & Views