How racism manifests itself in NGO culture and structures – part one: Deep structures

The Bond report Racism, power and truth: Experiences of people of colour in international development, released in June 2021, laid out the very real experiences of people of colour across the sector. In this blog series, we aim to build on the themes that came out of the report and to reflect on what we think has changed over the months since its release.

This is part one of two blogs looking at culture and structures inside of NGOs and the discrimination it exacerbates. You can read part two here.

Deep structures driving racism

Racism is structural

It’s embedded into all aspects of our society, so it’s impossible for our sector not to be deeply marked by it. In fact, “from overt experiences of racial discrimination, to everyday micro-aggressions and unsafe workplace cultures, nearly everyone had a story about how the dominant policies, practices and cultures have marginalised them.”

Every organisation has a strategy, structure and culture. We spend a lot of time discussing and developing our strategies and ensuring that our structures are “fit for purpose”.

Butdo we take enough care and spend the necessary time creating cultures that support people? Especially when we know that it is culture that underpins everything we do and how we do it? As management consultant and writer, Peter Drucker said, “culture eats strategy for breakfast”.

In the Bond report, we discuss a concept known as “deep structures” of an organisation.

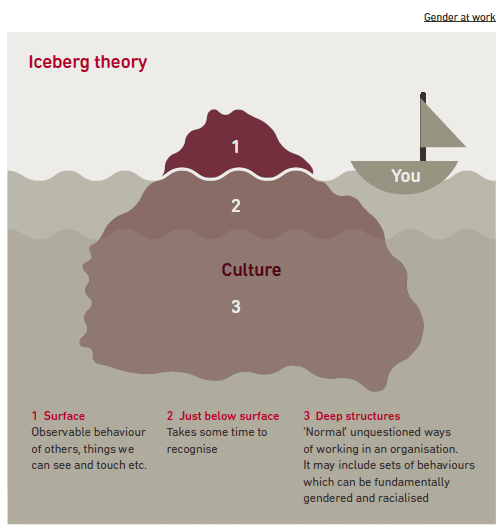

Imagine an organisation like an iceberg with 3 levels representing its organisational culture. Above the surface is level 1. This is what is visible of an organisation’s culture. This layer includes its name/brand/logo, the public statements it has made, the images and lexicon it uses, its organogram and job titles and so forth. This level is the projected image of organisations, what an organisation would like the world to see.

In level 2, we have the things that are just below the surface of the water. These are harder to recognise at first glance. These include how organisations and individuals interpret or put into practice the written values and written principles the organisation says that it subscribes to. Are they “walking the talk”? For some, this is the difference between theory and practice; between what we say, what we do and how we do it.

The last level is level 3, immersed under the water and much harder to detect. This is the vast “invisible” part of our culture, the part that is understood, and often accepted or tolerated, and yet is unspoken. This is the ‘deep structure’, which holds our assumptions of how the world works, our attitudes and our beliefs.

These are usually the unwritten rules that manifest themselves through both formal and informal power. By informal power we mean power wielded by individuals or groups that do not necessarily hold “senior roles”, but still hold significant power and influence over decisions and people. To be clear, unwritten rules are inequitable and harmful to the most marginalised people.

Deep structures can be so powerful that they override any organisational policies, commitments or formally approved, endorsed and sometimes publicised “organisational values and principles”, including those related to equity, diversity andinclusion. This is where the unspoken power dynamics reside, that are reproduced and sustained.

Through this image, we can get a sense of how much of our culture is invisible, and is not publicly acknowledged. Truly understanding this, and how the different levels interplay in our organisations, is a critical first step in a long and challenging journey towards transformational change and dismantling racist structures within organisational cultures.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Our weekly email newsletter, Network News, is an indispensable weekly digest of the latest updates on funding, jobs, resources, news and learning opportunities in the international development sector.

Get Network NewsThe Bond report on Racism, Power, and Truth explored the experiences of people of colour working in the international development sector, and shared the harmful and racist practices they experience which are rooted in deep organisational structures.

These experiences illustrate what happens in the “deep structure” level of an organisation, with incidents of power being used over staff of colour, comments and assumptions that go unchallenged, such as the assumption that having an “accent has a big part to play in getting roles in the sector. If you don’t sound ‘right’ you aren’t the right fit”. The “white gaze” in international meaning means that it is assumed that Southern Black, Brown and other people of colour are measured in capability against a standard of Northern/Western whiteness and that this measure finds them incomplete, wanting, inferior or regressive.

Through the work we did with the Bond team I came to understand that addressing the deep structural unquestioned ways of working that underpin racism in an organisation is much more than a process. It is a way of life and an attitude of mind which makes every day an opportunity to get more insights and work for change.

Rob Williams, CEO at WarChild

Commenting on the lack of support they received in their role, one survey respondent said: “In terms of support and supervision, I felt that my manager was unsure how to relate to me compared to my white colleagues in a similar position, therefore I felt I had slightly less supervision/support.”

The lack of support for people of colour to progress within organisations means that they do not reach senior roles, and if they do so, deep structural issues significantly limit their ability to shape culture and drive change. One respondent wondered:“Where are all my role models? Senior managers in my organisation are about 95% white. I’ve been looking for a mentor who looks like me for almost two years, but they are few and far between.”

Nothing is more present and recurrent than the microaggressions that take place in the deep structures of our organisations. One survey respondent shared: “[I’ve had] a mix of microaggressions, bullying and outright racism and xenophobia [from my managers] over the years.”

The impact of these harmful experiences on people of colour can be long-standing and damaging to not only mental health, but physical health as well.

As we start to recognise and understand the deep structures in our own organisations, we can become better equipped to move to action to dismantle racism.

We mustacknowledge the depth of work that needs to be done to achieve racial equity, redressing power dynamics and addressing racism in our organisations and work. This will mean rather than opting foreasier transactional initiatives and solutions that skim the surface, we need to commit to going deeper to the systemic shifting solutions that get to the root of the problems.

In part two of this blog, we will unpack the difference between anti-racism and EDI and why we must be aware of this difference in approaches to EDI.

Category

News & ViewsThemes

Anti-racism